Francine Savard - A Documentary Exhibition

2025 | FRANCINE SAVARD

A DOCUMENTARY EXHIBITION

TORONTO

Jan 15 - Mar 7, 2026

Opening reception: Thursday January 15, 2026, from 6pm-8pm

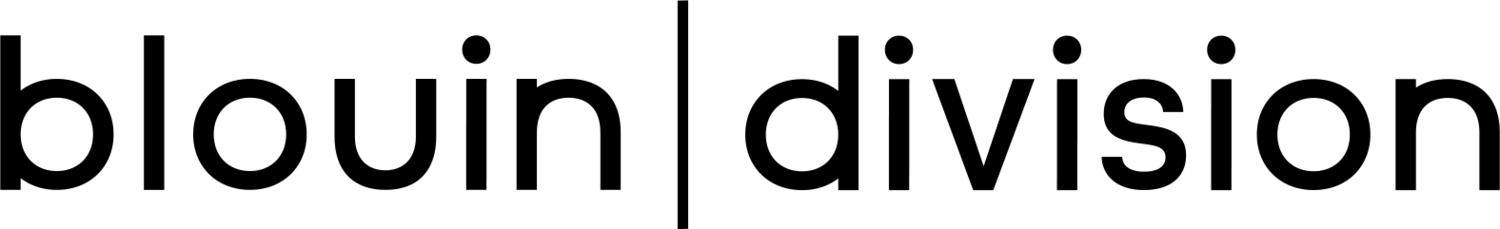

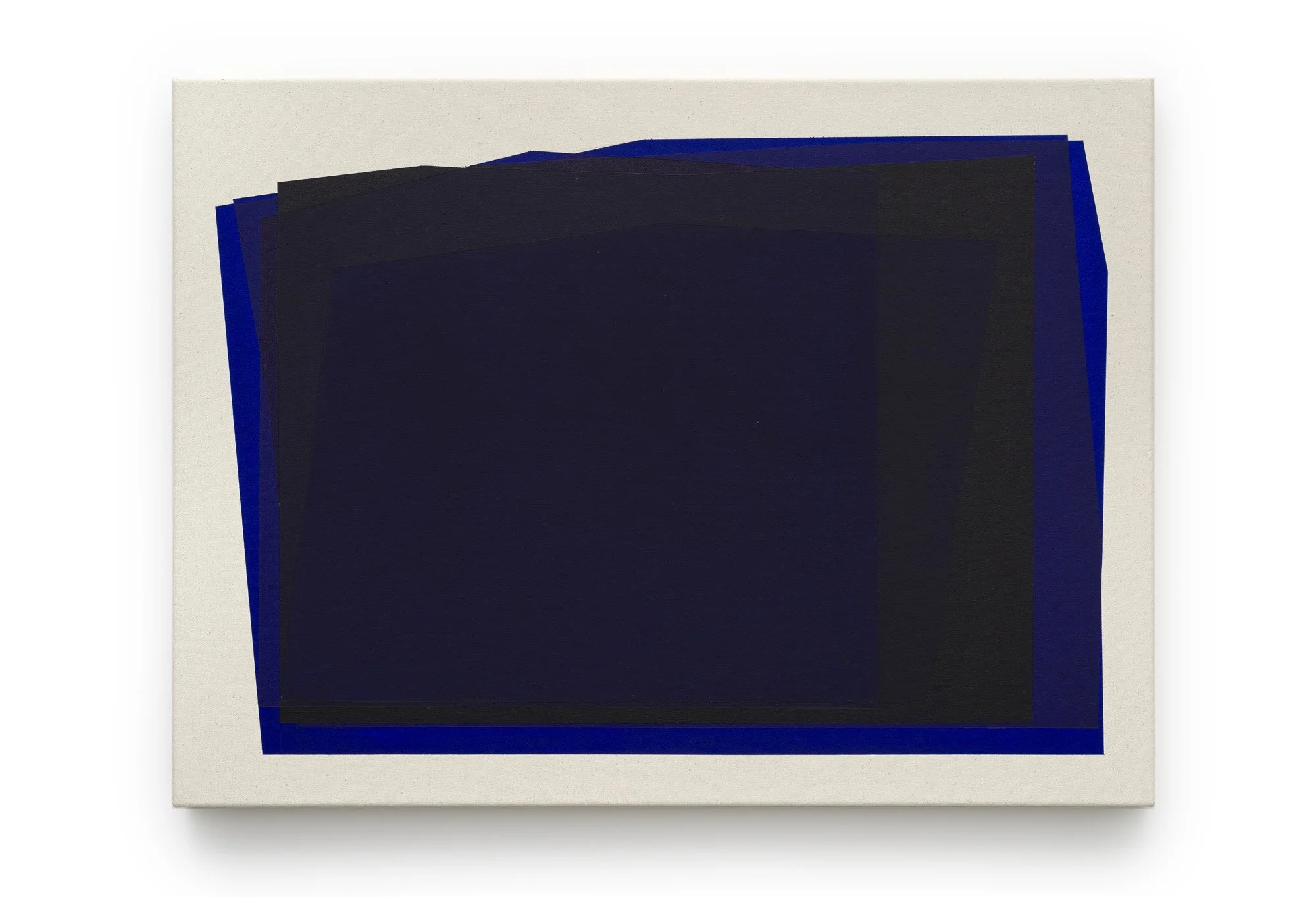

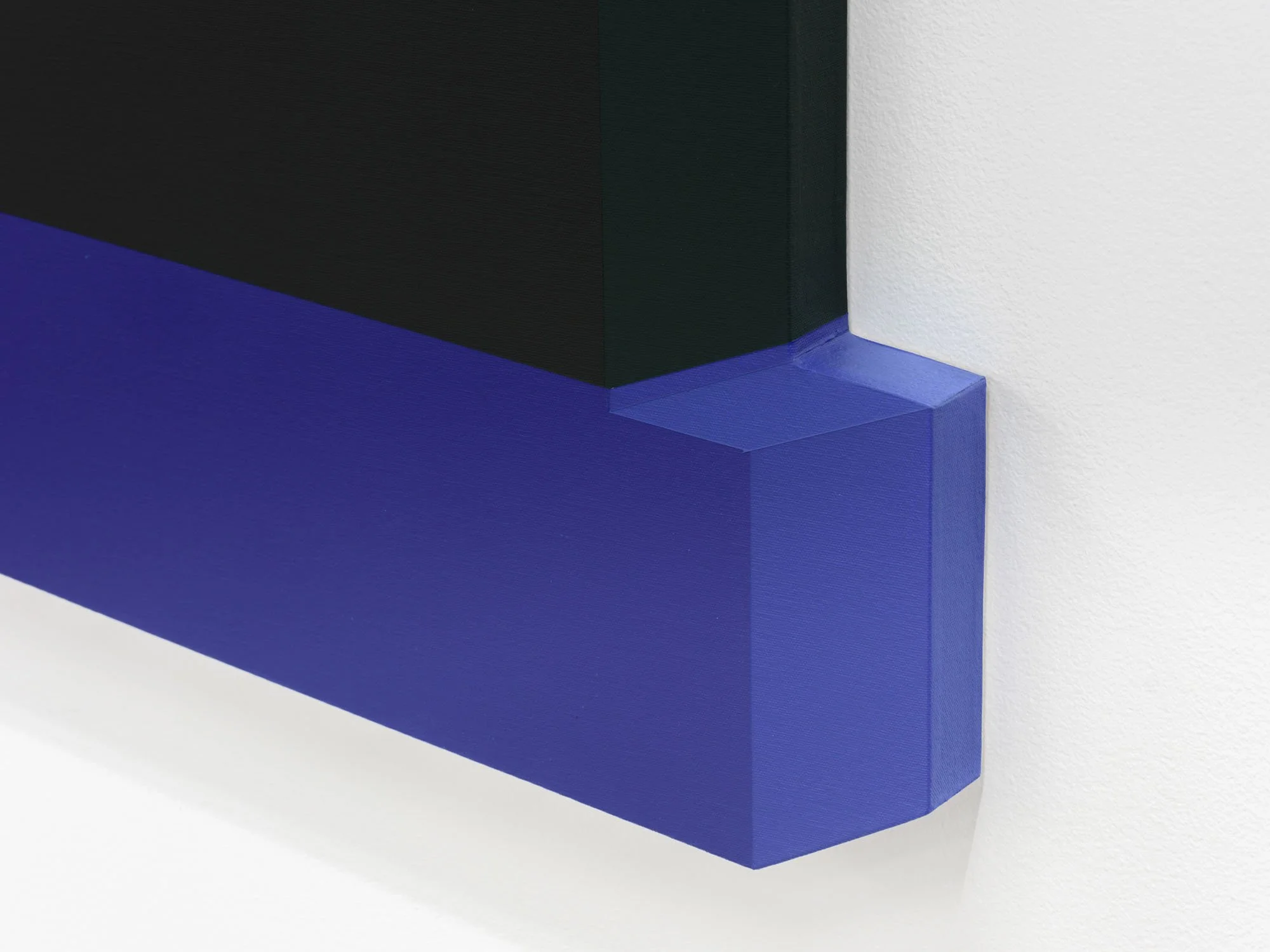

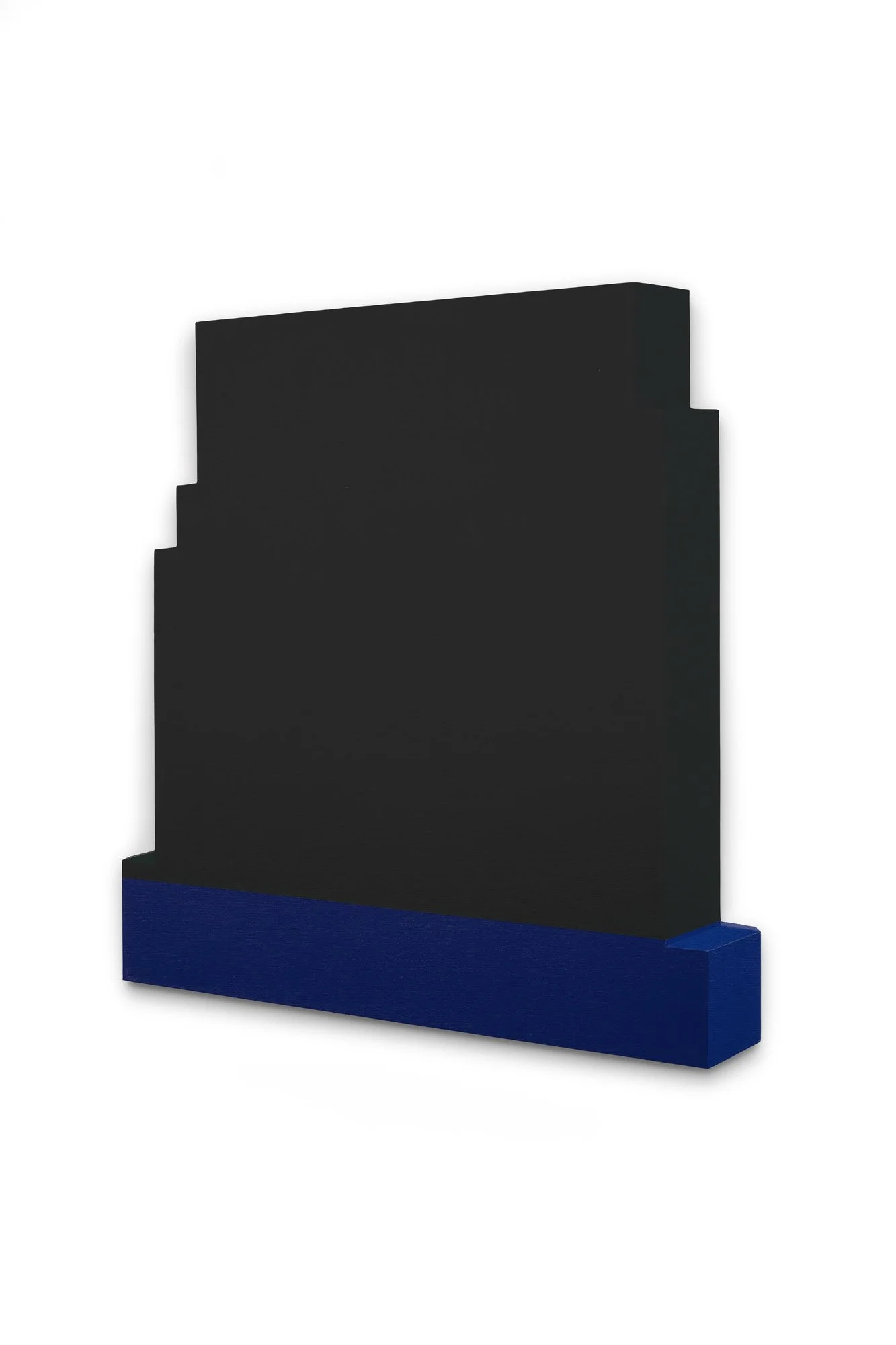

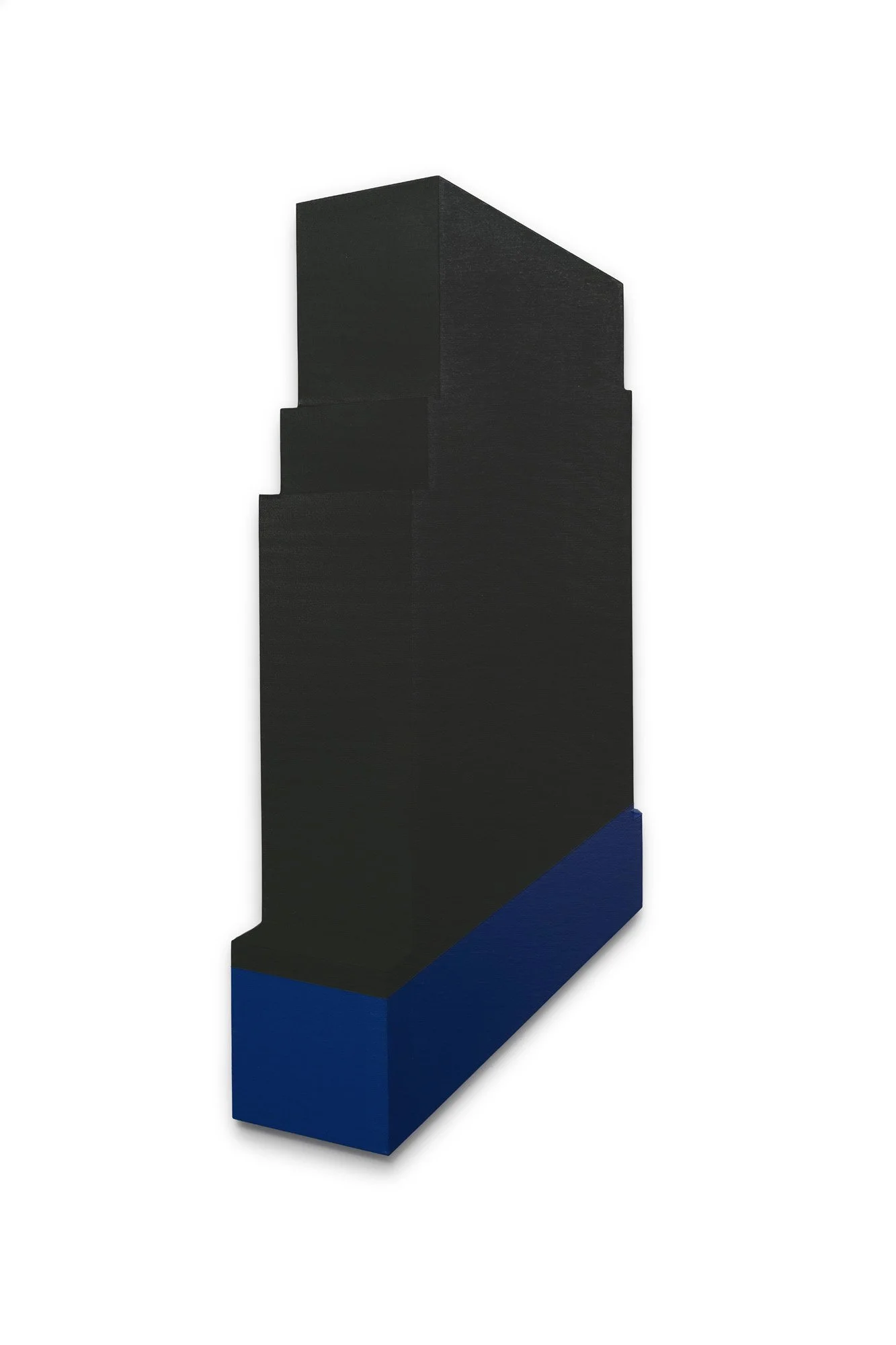

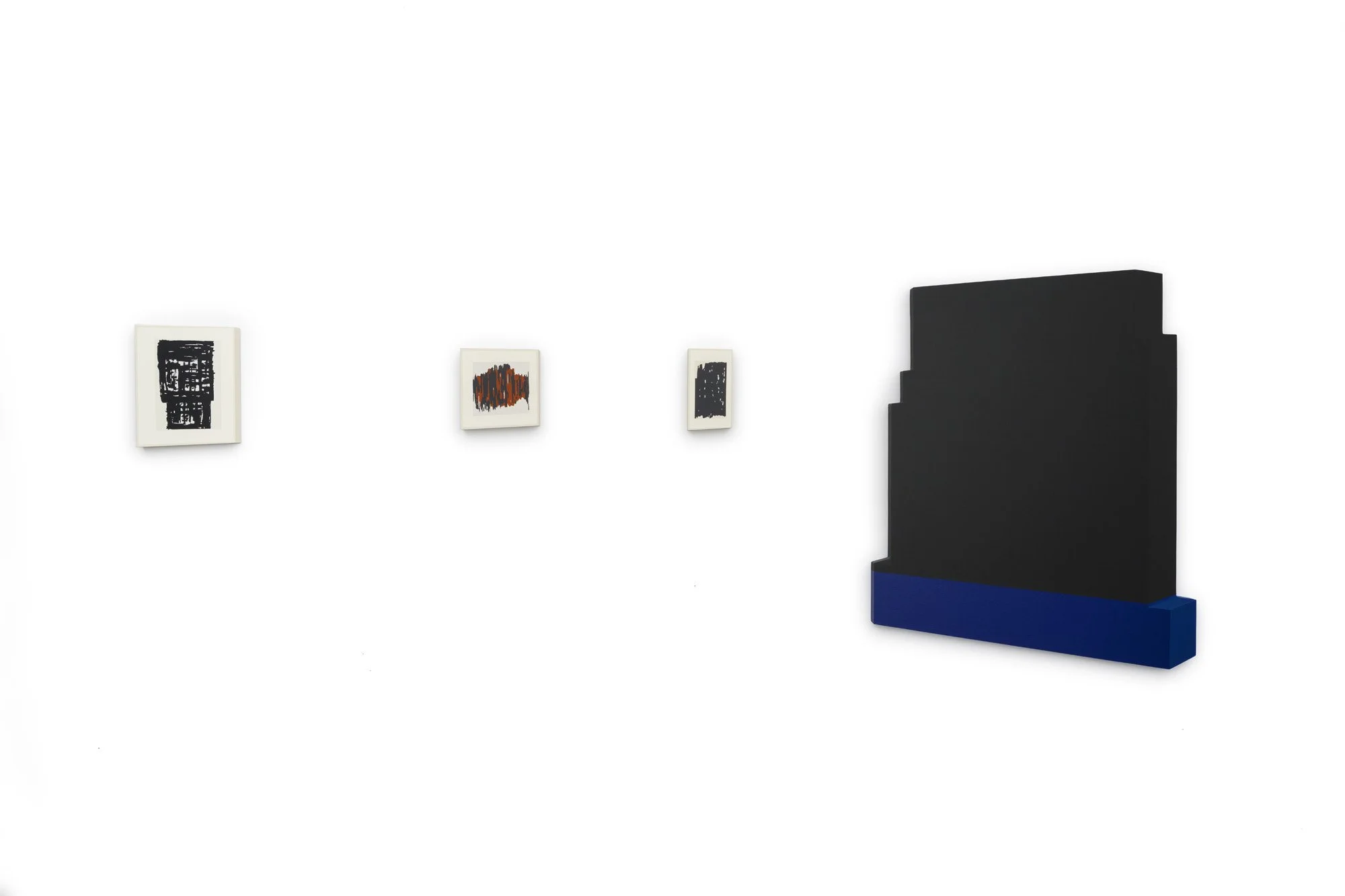

Francine Savard, Legacy, view 1 and 3 inks (Anne Truitt), 2025, Acrylic on canvas mounted on panel From left to right : 30.5 × 24.6 cm (12" × 9.7") ; 20.3 × 19.6 cm (8" × 7.7") ; 20.3 × 11.2 cm (8" × 4.4") ; main painting : 101.6 × 73.7 cm (40" × 29"), Together : 101.6 × 261.6 cm (40" × 103")

A Documentary Exhibition presents Francine Savard’s latest research.

This exhibition mainly features two series of ‘studies’ carried out specifically around the works Landfall (1970) and New England Legacy (1963) by American artist Anne Truitt (1921–2004).

My fervour for studying Anne Truitt’s works stems from my frustration at never having seen any of them (I have seen works by Judd, Flavin, LeWitt . . ., Buren, Morellet . . ., but never by Anne Truitt). This research activity has occupied me on and off since 2014. For me, it is the never-ending continuation of the ‘painting lessons’ (a research programme I established for myself in 1994 after completing my master’s degree in visual arts at UQAM). These ‘lessons’ gave rise in 1998 to Les couleurs de Cézanne dans les mots de Rilke [Cézanne’s Colours in the Words of Rilke], in 2000 to the series Un plein un vide [Full Empty] about Fernand Leduc’s paintings from 1955–1969, in 2018 to the paintings of Programme d’œuvres en devenir de Paul‑Émile Borduas [Paul-Émile Borduas’ Programme of Works in Progress] inspired by his late drawings, and in 2019 to Montréal 84, works based on an exhibition catalogue by Belgian artist Marthe Wéry. Each time, these ‘painting lessons’ are an opportunity for me to open a virtual laboratory in the studio of the respective artist under ‘investigation’.

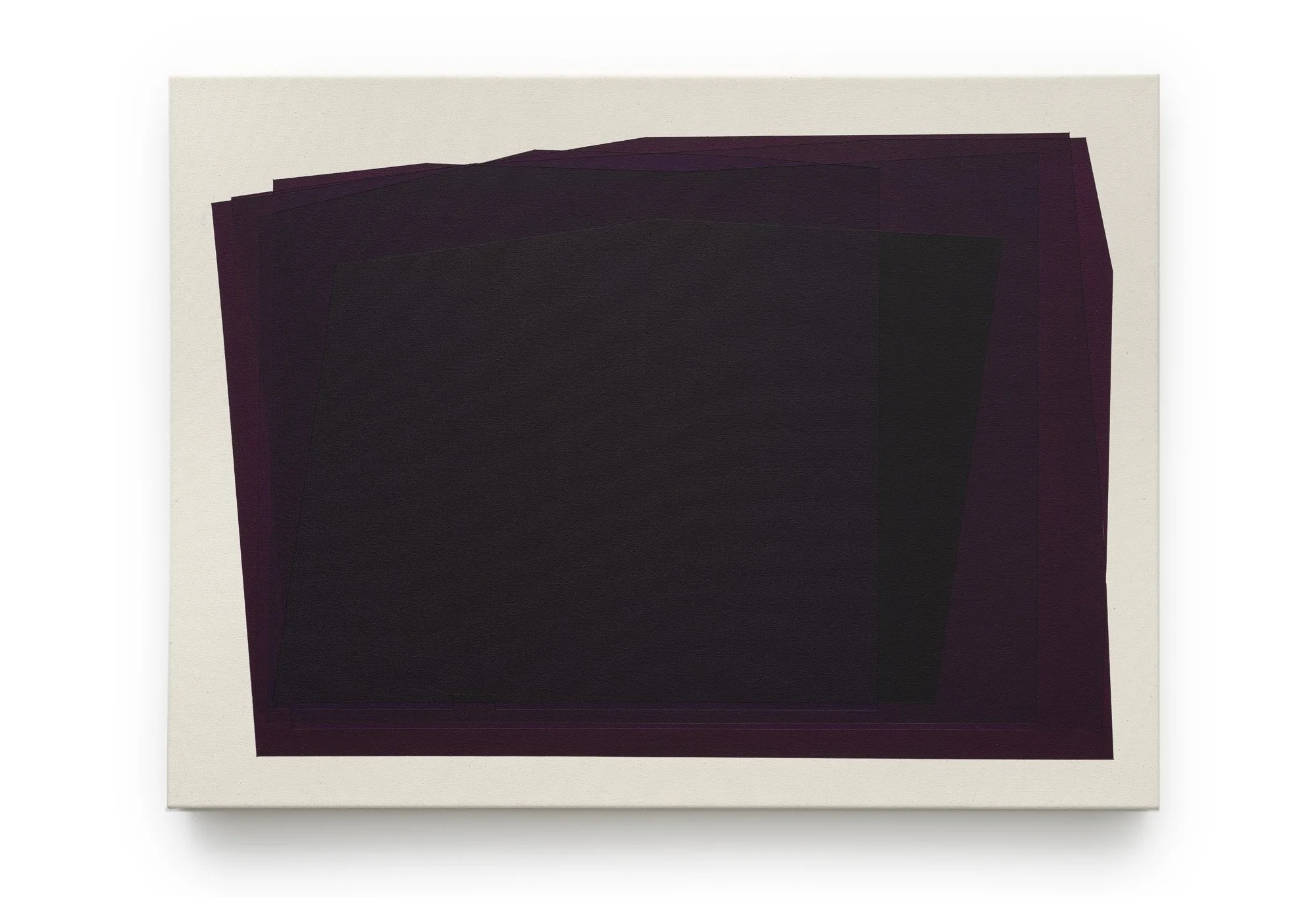

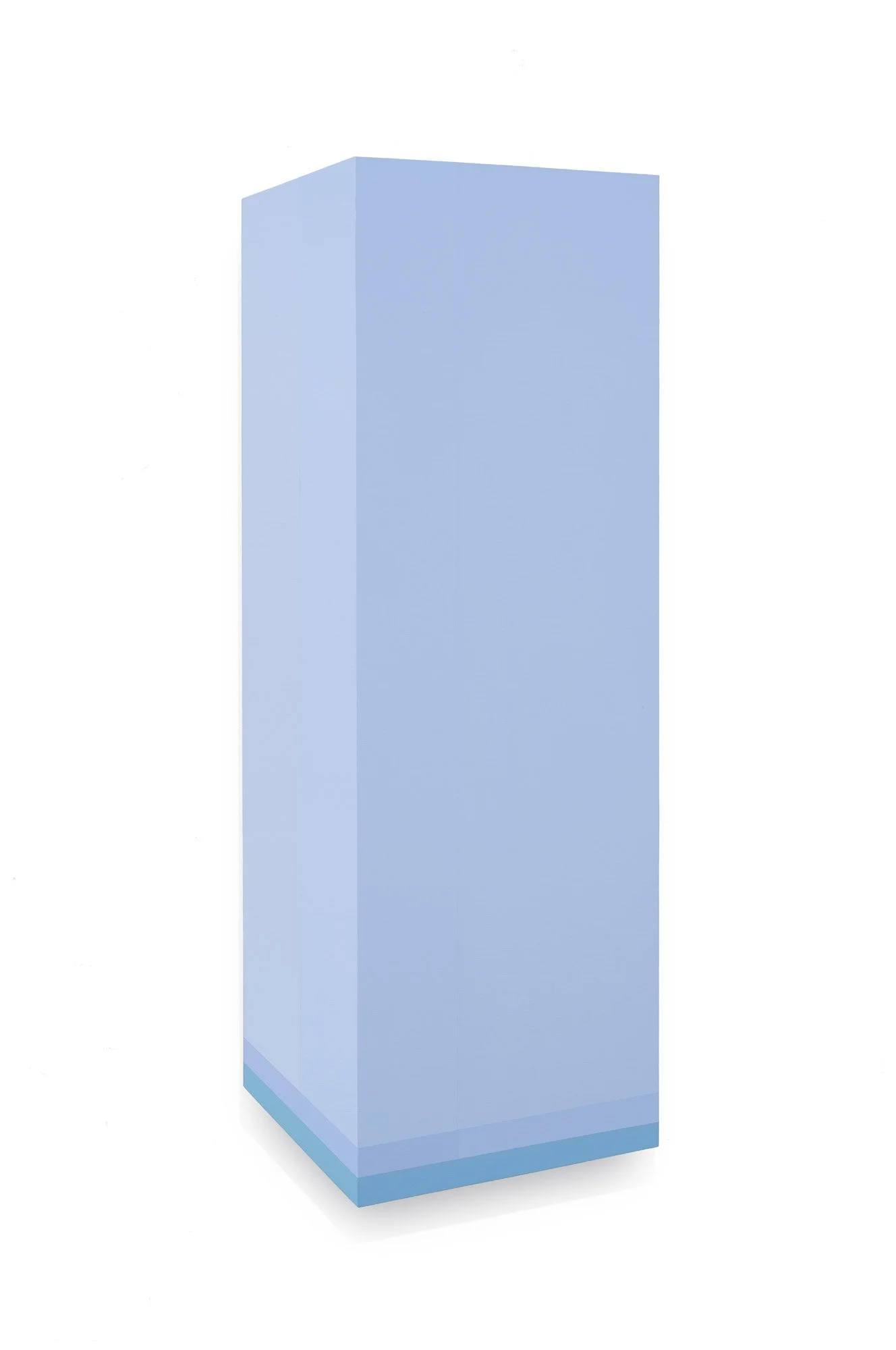

Anne Truitt’s unique sculptures are often human-sized parallelepiped shapes made of wood, with surfaces painted in sumptuous multi-layered colours and compositions cleverly offset from the underlying structures.

Rather than minimalism that responds to Frank Stella’s tautology, ‘What you see is what you see,’ Anne Truitt’s works correspond, in my terms, to a ‘loaded’ minimalism, influenced by landscape or biographical reminiscences that provoke an openly narrative emotional response in the viewer.

The visual sophistication of her pieces suggests that they are not only sculptures, but also three‑dimensional paintings, meaning that they are particularly affected by light. Anne Truitt describes her painted objects as colour liberated in real space.

For someone who has not seen Anne Truitt’s works in person, the available information is sorely inadequate. Even when there is a wealth of documentation, as in the case of Landfall, the abundance of photos and texts only multiplies the questions raised by the work, making it impossible to establish a reference point. As Lesley Johnstone wrote about my practice: ‘Words serve as both a gateway and an obstacle.’ In the context of this research, the same will be true of photography, because these works resist representation and are, as Kristen Hileman points out in the catalogue Perception and Reflection, almost impossible to photograph. Because I lack the experience of face‑to-face contact, the recent paintings brought together here constitute a loving ‘account’, one that is speculative, always in need of verification, and provoking in me a lasting fixation, the driving force behind my stubborn creative research.

— Francine Savard, January 2026